I have on my shelf, an autographed copy of General Obasanjo’s ‘My Command’ which gave his account of the unfortunate civil war. I also have General Madiebo’s (un-autographed) version of the war.

Between these two extremes, I have read other authors who have made their valuable and invaluable contributions to enrich our knowledge as to what really went on during those three years of madness. So why would another book on the civil war interest me; a war that ended over 40years ago and from which we have refused to learn any tangible lesson?

General Alabi-Isama is someone I have liked almost from the first time I met him. He has also been talking about this book for at least a couple of years now. He was gracious enough to give me a draft copy to flip through. To top it all, he had given me more than an advanced notice of the launch.

So when Uncle Sam Amuka called me a day to the launch for details, I had more or less made up my mind to attend. The fact that the venue was less than 15 minutes drive from my house was an added incentive. I pleaded with Uncle Sam to show up if only to ‘shake hands and disappear’ as he sometimes does.

To my surprise, he was not only there before me, he stayed till the very end. When I signalled to him at a point that I wanted to leave, he waived me back to my seat.

The programme started almost on the dot which was a welcome surprise despite the slightly inclement weather. Another surprise was the quantum—and quality of attendees. Many old Generals—some leaning heavily on walking sticks-graced the occasion and stayed the course.

They were ably led by General T.Y Danjuma who doubled as Chairman and Chief Presenter. Their use of nick names and aliases in addressing themselves was enchanting and indicative of old camaraderie.

I am sure it was more than a reunion of sorts for these old generals. It was however, not only the Generals that graced the day. Many otherwise busy VIPs and veteran journalists were there too.

At the end of it all, Uncle Sam echoed my thoughts when he wondered what it was about ‘our friend’ that brought all these people to the hall. He repeated the question twice but I could not think up a good answer.

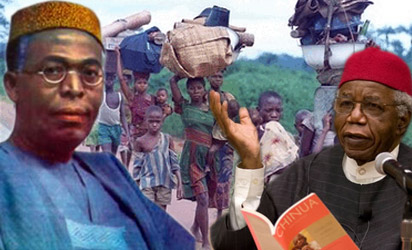

My answer ‘came’ a couple of hours later when I got home and decided to browse the book. I found myself spending the next two hours. It was that riveting. But what got me was the man’s attention to details. Pictures, maps and documents authenticated the fact that General Isama not only took part in the war, he was a major participant.

In spite of what many of us were made to believe, the real truth about each officer’s role in the civil war is known to many of the officers of that era. So their presence was possibly to identify with the author and give their approval of the ‘corrections’ that have been made.

Secondly, anybody who keeps records and provides minute details the way General Isama has done, can not be described as flippant, a fact that might be overlooked by those of us who only know the social side of him.

It was probably this attention to details that made him reach out to many officers that played a role in the war. As to the rest of us who filled the hall, the social, amiable side of him probably won us over.

The book from what I have read- and I have read more than half—gives a more believable account of what happened during that dark part of Nigeria’s history than many books on the topic including international ones. It shows that truth, whether hidden for 40 or 400 years, will one day eclipse untruth.

Thanks to the book, we get to know a bit of the personalities of those who took decisions –either in the war front, or in their offices that affected the outcome of the war. We also got an insight into the politics, intrigues and indiscipline of our young generals; how the war officers and desk generals—as Wole Soyinka once described them, took decisions that perished lives.

I was touched as I am sure many at the hall would have been, at the presence of many unsung war heroes; the barely literate tank driver whose tank sank on the bank of a river, the tribal marked tank commander who was mobbed by the enemy, the colonel who virtually started the war and was there throughout the duration of the war, the officer who actually received the enemy surrender, and wives of those who had passed on.

You wonder why very little capital has been made of these unsung heroes. Why is it that those who are at the fringes of things in Nigeria are those who benefit the most? They are the ones who have streets named after them, who collect the nation’s most coveted awards while laughing to the bank.

Mean while the real heroes are left to languish like Brigadier Adekunle who gave his all to the war effort. Today, he is dying slowly; a poor, neglected and dejected person. The same thing has happened to June 12 where the fringe players have cornered most of the spoils. We hope the real story of June 12 with its many heroes and infidels will emerge soon.

I salute General Isama’s courage and urge all of us, especially those who are playing brinksmanship in River State, to sometimes remember how we came to fight this mindless war.